INTRODUCTION

As a standard within museums today, objects and exhibits are primarily presented to appeal to the viewer’s visual sense. This can pose as a significant barrier between the viewer and their depth of understanding of an artefact. In some cases this also limits a person’s capacity to experience an object as it was originally intended to be experienced. Museums oftentimes lack variety in sensory experiences and can find difficulty in reaching audiences who require more than just visual stimulation to learn. On the other hand, there are museums which have altogether too much sensory stimulation in the eyes of those sensitive to such things. These effects are significant barriers to learning and present “an obstacle to civil engagement” within museums, but thankfully there are actionable approaches which can be taken to alleviate these problems (Fletcher et al., 2018:67).

This essay will explore the relationship between customised sensory experiences and their capacity to facilitate deeper object connection and overall museum satisfaction and appeal to people of varying age ranges and capabilities. Three different case studies are examined of current research focused on methods aimed at helping museums appeal to all of the senses. It is proposed that museums can in fact appeal to all of the senses, reaching audiences on all spectrums, through the development of carefully researched and tailored multi-sensory experiences by using a combination of methods such as hands on experiences with artefacts, sensory gallery guides, and augmented reality technologies.

OVERVIEW

Before attempting to address how museums can appeal to all the senses, terms used in this essay and historical background on the subject will be outlined. For the purpose of this essay the phrase “people with sensory sensitivities” will cover those considered to be on the spectrum for autism, those with learning disabilities, and/or those with physical disabilities. People who fall under this umbrella have been deeply considered in the following discussions. To begin, the history of sensory experiences within museums starts in the 17th and 18th centuries, where museums were a place in which people could touch objects more freely (Howes, 2018). Howes describes a scene in which visitors to places such as the British Museum were allowed to “heft, shake,…sniff and even gnaw on objects in a collection” (2018:319). It was thought that objects should be manipulated and touched so that “scholarly inquiry” could be facilitated (Howes, 2018). Museums have become quite the opposite today and are now places where “see, don’t touch” is the standard mode of operation for visitors. Though many museums today are making efforts to develop hands on activities, some still lack this aspect completely. In the process of creating such hands-off environments, museums have closed off an avenue for transmitting information. Since in recent years the expectation for museums to uphold a certain level of social responsibility to their communities has risen, now is the perfect time to strategise new methods for providing enriching experiences to reach wider audiences (Marques and Costello, 2018:543).

METHODS

Supervised handling sessions

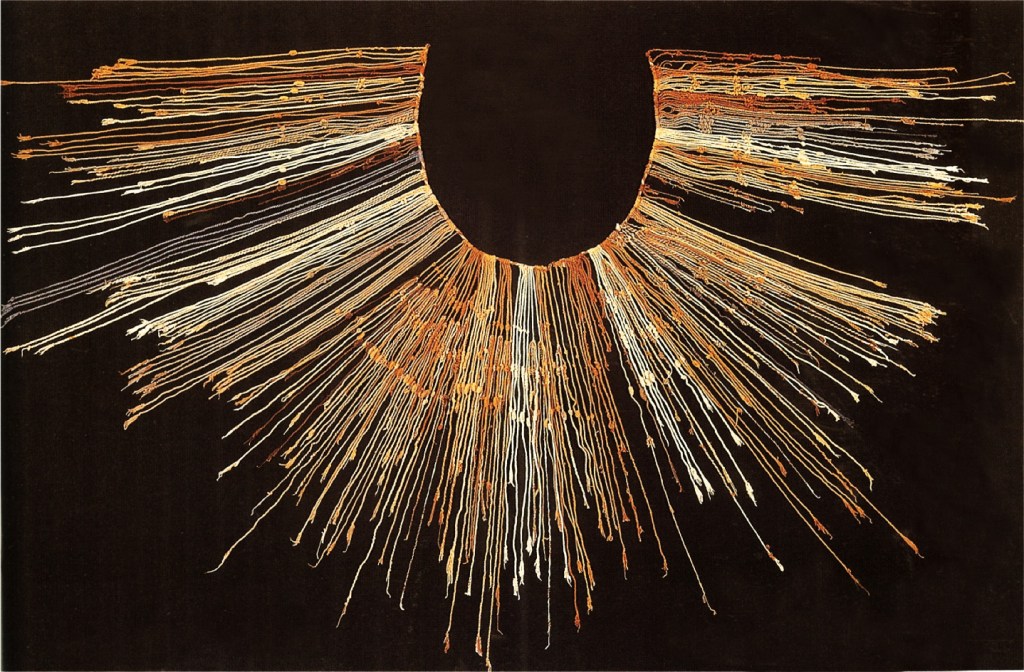

A method with significant potential is that of allowing supervised handling sessions with the aim of facilitating deeper object connections and a chance to experience an object as it was originally intended to be interacted with. Touch is an invaluable sense in learning. Introducing a sense of touch would add one more data point to a person’s understanding of the true nature of an artefact. In addition to this, we must consider that across cultures people appreciate objects and aesthetics in more ways than just visual, ie: objects like a Japanese scroll or Inca quipu are meant to be handled to be understood. A study published in 2018 called “Sensing art and artefacts: Explorations in sensory Museology”, conducted research into the impact of object handling sessions after participants viewed the objects via digital photographs online. The research began with positing a scenario in which someone from the West might approach attempting to understand an object like an Inca quipu. A quipu might look to a Westerner’s eyes like a colourful necklace of strings with random knots throughout, but in reality it is “a highly intricate form of writing which engages touch and rhythm in the tying of the knots and involves a wide range of colours and patterns” (Howes, 2018:318). Such an object lying flat in a case, does little to nothing for the interpretation of it.

With the thought in mind that some objects need to be touched to be understood, the researchers created experiences to gauge what effect opening up objects to further sensory exploration would have on a person’s connection with the object and their understanding of its meaning. Through four case studies of facilitated handling sessions with people from various academic backgrounds, nearly every person reported experiences which were much more personal and in-depth than what they had experienced just from viewing the object. Upon immediately seeing a particular bronze Victorian ‘magic’ mirror in person, one participant described it as “astonishing” as she took in the details (Howes, 2018:325). She went on to report surprises as to the reality of handling the object versus what her expectations were (Howes 2018). Most uniquely of all she experimented with shining her phone flashlight onto the mirror in an attempt to reflect onto a nearby wall the hidden image within the ‘magic’ mirror. She succeeded in this and “wondered when the last time that the image had been formed”, finding herself excited to be holding something in the same way as its owner in the past had done (Howes 2018:326).

From this case study the value of additional sensory input to objectinterpretation can easily be seen. The woman interacting with the Victorian mirror had an unparalleled experience for herself by creating a situation that placed her in a moment which reflected that of one from the object’s own past. She came to know the ‘true nature’ of the artefact through hands on interaction with it. Giving people the opportunity to manipulate an artefact as it was designed to be manipulated can create a metaphorical bridge between the past and the present and provide a depth of understanding not achievable from a view-only gallery display. Additionally, object handling sessions can benefit both those who need touch sensory input to learn, or those who are blind or low-vision. An obvious argument against object handling is the potential wear and damage to them. Risks and benefits will need to be weighed before any objects are handled. For objects too sensitive for handling, an alternative is to create replicas to instead deliver the original object’s message. Allowing objects from a museum’s collections (or replicas of them) to be handled would engage more of the senses, extend learning opportunities to more people, and deepen participant’s relationship with the past.

Full paper can be found on my Academia profile here

Featured Image source: Quipu, Zach Zallium 2011