Report Layout Sample

OVERVIEW

Artefact “DUROM.1960.2846”, which will be referred to as “2846”, is a jade pendant currently in the possession of the Oriental Museum in Durham, England. It was donated to the museum by Sir Charles Hardinge. Comparative analysis places its likely origin in the Chinese Qing Dynasty. Non-invasive X-ray fluorescence (XRF) was performed on all parts of the pendant. The term “burnt jade” was explored to better understand the stones’ possible manufacturing technique. Furthermore, through the lense of Chinese history, evidence has been gathered to support the possible use and symbolic meanings of the artefact.

ACQUISITION & PROVENIENCE

Object “2846” belongs to a collection of artefacts received in 1959 by the Oriental Museum of Durham University by Sir Charles Hardinge. Hardinge began collecting artefacts in 1917, focusing particularly on Chinese jade. Alongside keeping meticulous acquisition records, Hardinge wrote a book on jade called Jade: Fact and Fable. Durham University published this volume as part of a deal with Hardinge for the bequeathment of his jade collection upon his death. The collection arrived at the University in 1959, before the opening of the Oriental Museum in 1960.

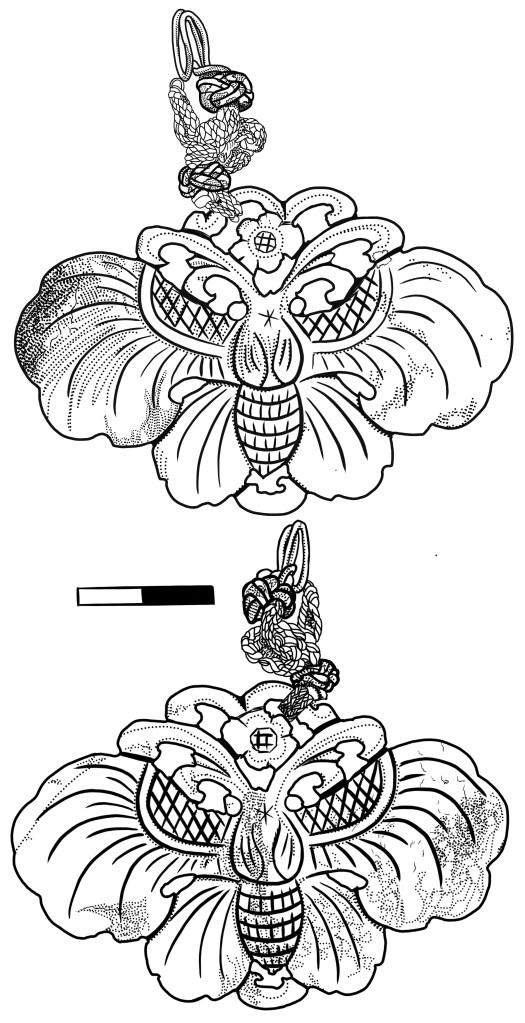

Hardinge purchased “2846” on July 9th, 1935 in London from a “William Williams” and gave it the catalogue number “2846”. He originally had this catalogue number listed as a “Grey Jade [?] plaque for a gong, bats and clouds outside the floral design the other” but this was crossed out and above it written “& hanging piece carved as a butterfly in Burnt Jade”.

MATERIALS

Historical Background

The term jade is used in English to categorise hard gemstones, including the stones jadeite and nephrite. This term originates from when the Spanish encountered the green stone used by the natives of Mesoamerica and named it piedra de ljada, or “stone of the loins, from the French pierre l’ejade”, which then became le jade (West, 1963:3). Later this term was applied to stone carvings arriving in Europe from the Orient in the 17th century (West, 1963:3). In China the character for jade, yù/玉, has been used to describe “any hard beautiful stone”, including cornelian, pudding-stone, soapstone, etc., since the beginning of the Chinese writing system, extending into the first millennium AD (Forsyth and McElney, 1994:28).

Social Significance of Jade

Yù/玉, or jade, as it will be referred to it in this report, has been highly regarded in China for over 7,000 years. This is evidenced by jade working stretching back to Neolithic times during what scholars are beginning to call a “Jade Age” in China from 4000 to 2000 BCE (Forsyth et al.,1994:28). It was worn by kings and nobles, displaying a person’s high social status. Early thoughts were that jade had magical properties to “protect the body from decay” so it was often used in burials (Khan, 2020). In later times jade was prized for its connection to antiquity so many ancient forms and designs were copied during the Ming and Qing dynasties (Khan, 2020).

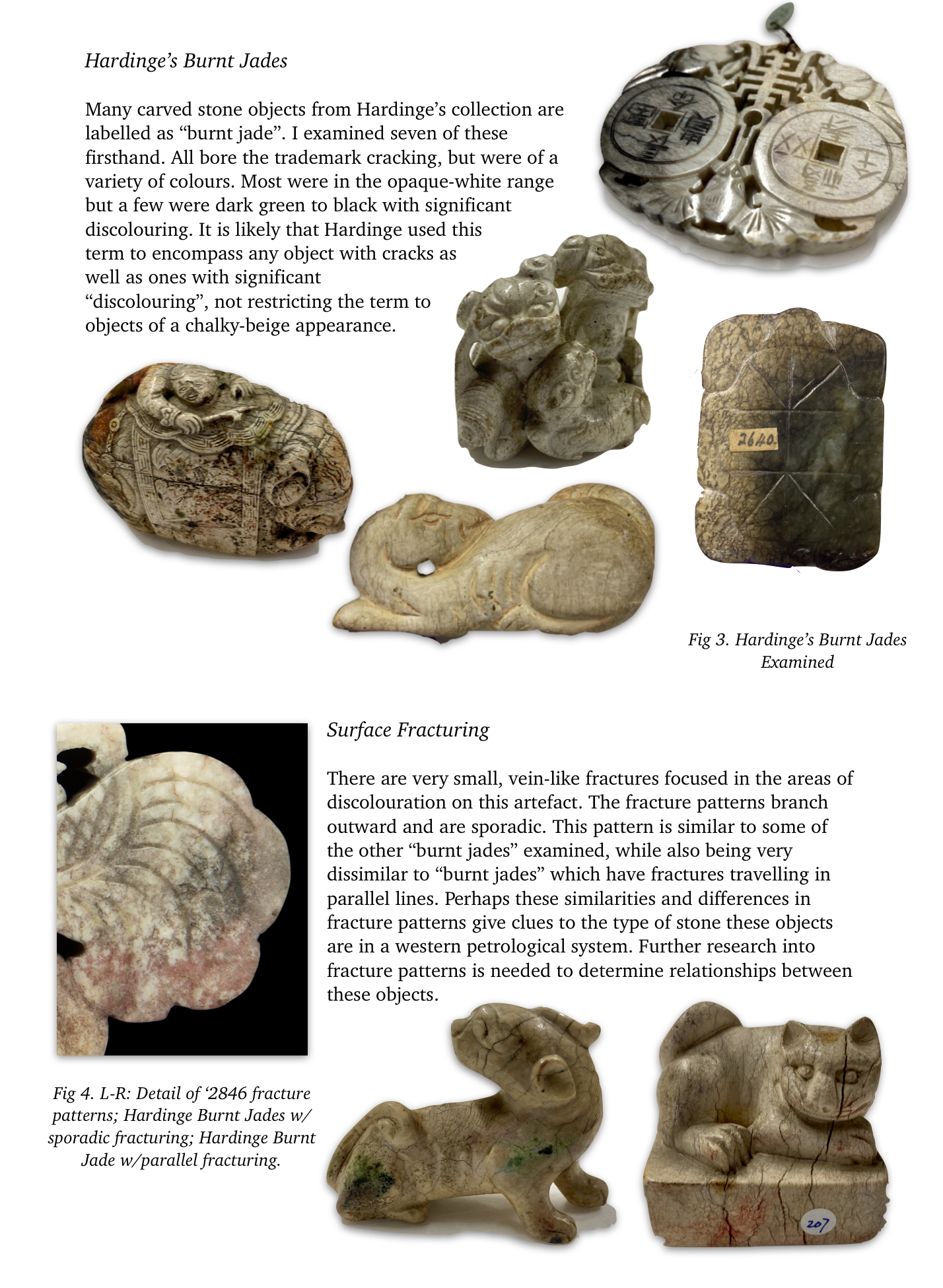

“Burnt Jade”

This particular object has been labelled as “burnt jade” by Hardinge. This term is often used to describe jade with “an opaque chalky appearance, usually with minute cracks all over the surface” (West, 1963:4). Burnt jade is also linked to what is known as “chicken-bone” jade, which is a trade name typically referring to jade with an “ivory-like appearance” and/or “jade with an opaque white to very light brown or grey; [that] may have been buried or burned” (Keverne, 1995:27)(West, 1963:5). There are two possible methods through which scholars believe this look was achieved; the most common being that of extreme heating of nephrite. The Hunan Provincial Museum describes this process of “fire burning” thusly:

“the stone is coated with sodium hydroxide, wrapped in calcium oxide (lime), and smouldered in sawdust for two days. The chicken bone is white when removed. If you dip in cold water while it is hot, it will produce cow hair lines”

Yu, Yan- 喻燕妓 (2020)

Methods using electric technology can reach a similar effect as demonstrated in an experiment at the Freer Gallery Laboratory, where both white and blue-green nephrite were heated to 1025C and resulted in the trademark chalky-beige/cream colour (West, 1963:5). The

Fig 2. Yu (2020) Burnt Jades conductor of the experiment, West, also suggests that “chicken-bone” jade could be ascribed to decomposition in a burial environment (1963:5).